Introduction

A Rigid Frame System is one of the most widely used structural solutions in modern construction, supporting everything from warehouses and factories to sports halls and large commercial buildings. Engineers rely on it because it combines structural strength, lateral stability, and design flexibility in one integrated framework. Understanding how a rigid frame system works helps owners, designers, and builders make informed decisions about space planning, load performance, and long-term value. In this article, you will learn what a rigid frame system is, how it performs, where it is applied, and why it remains a trusted choice across industries.

What Is a Rigid Frame System?

Definition of a Rigid Frame System

A Rigid Frame System is a moment-resisting structural framework where beams and columns connect through rigid joints. These joints resist rotation, so the angle between members stays nearly constant under load. Because of this behavior, the frame acts as a single unit rather than a set of separate parts. Loads move through bending and shear within the members, not through hinges or braces. This structural concept allows the frame to carry both vertical and horizontal forces efficiently. It forms the backbone of many steel and reinforced concrete buildings.

How Rigid Frame Systems Differ From Other Frame Systems

Rigid frame systems differ from simple or braced frames by how they achieve stability. Simple frames allow rotation at joints, while braced frames depend on diagonal members for stiffness. A Rigid Frame System relies on joint rigidity instead. The stiffness of beam-column connections provides resistance to movement and deformation. This approach eliminates the need for interior bracing and keeps the structural layout clean. As a result, the building gains structural integrity through connection design rather than added structural elements.

Core Structural Purpose of a Rigid Frame System

The core structural purpose of a rigid frame system lies in balancing wide, unobstructed space with reliable load resistance. By relying on rigid joints instead of auxiliary bracing, the system achieves stable force distribution, predictable deformation, and long-term adaptability across a wide range of building types.

| Structural Objective | Technical Explanation | Typical Applications | Key Technical Indicators (Common Ranges) | Design & Engineering Considerations |

| Large clear-span capability | Rigid beam-column connections resist bending moments, allowing long spans without intermediate supports | Warehouses, hangars, sports halls | Clear span commonly 20–90 m (steel rigid frames) | Member depth and stiffness govern span efficiency |

| Open interior layouts | Absence of interior columns enables flexible space planning | Logistics centers, exhibition halls | Bay spacing often 6–12 m | Early coordination with architectural layout is essential |

| Global structural stability | Frame action distributes loads across multiple members | Multi-bay industrial buildings | Global frame stiffness controlled by Σ(EI/L) | Uneven stiffness can lead to drift concentration |

| Efficient force distribution | Loads transferred through bending and axial forces rather than localized bracing | Buildings with variable live loads | Bending moments (kN·m) shared across joints | Accurate joint modeling is critical in analysis |

| Lateral load resistance | Rigid joints provide inherent resistance to wind and seismic forces | Low- to mid-rise commercial structures | Inter-story drift limits typically 1/300–1/500 | Drift control often governs member sizing |

| Long-term adaptability | Structural system supports future layout or load changes | Owner-operated industrial facilities | Design live load allowances often 10–20% above initial use | Future expansion loads should be defined early |

| Structural reliability | Redundancy through continuity reduces sensitivity to local overload | High-reliability facilities | Load redistribution capacity improves safety margin | Detailing quality directly affects redundancy |

| Integration with building systems | Clear spans simplify routing of HVAC, cranes, and services | Manufacturing plants | Crane loads commonly 50–250 kN per wheel | Secondary loads must be included in frame design |

| Lifecycle performance | Stable stiffness minimizes long-term deformation and maintenance | Long-life infrastructure buildings | Typical design life 50 years | Corrosion and fire protection strategies are key |

Tip:For B2B projects, the true value of a rigid frame system emerges when spatial requirements, future load growth, and service integration are defined early. Aligning these functional needs with frame stiffness and joint design helps ensure the structure remains efficient and adaptable throughout its full service life.

Key Structural Components of a Rigid Frame System

Columns and Beams in a Rigid Frame System

Columns and beams form the primary load-carrying skeleton of a Rigid Frame System. Columns transfer forces downward to the foundation, while beams span horizontally to support roofs and floors. Their size and shape control how the frame handles bending and shear. Tapered or deep members are often used where forces are highest. Together, these components create a continuous structural path. Their interaction defines the strength and stiffness of the entire frame.

Rigid (Moment-Resisting) Connections

Rigid connections are the defining feature of a Rigid Frame System. These joints are designed to resist rotation and transmit bending moments between beams and columns. When loads act on the structure, the joints force members to bend together. This shared behavior increases stability and reduces localized stress. In steel systems, this often involves welded or bolted moment connections. In concrete systems, it relies on monolithic casting and reinforcement continuity.

Load Transfer Mechanism Within the Frame

Load transfer in a Rigid Frame System follows a clear and continuous path. Vertical loads from roofs and floors move into beams, then into columns, and finally into the foundation. Lateral loads spread through bending moments across connected members. Because the frame acts as a whole, forces do not concentrate in one location. This unified behavior improves predictability and structural performance. Engineers value this clarity during analysis and design.

How a Rigid Frame System Works Under Load

Vertical Load Resistance

A Rigid Frame System handles vertical loads through bending and axial forces in beams and columns. Dead loads from the structure and live loads from use distribute evenly across the frame. Beams bend under load, while columns carry compression downward. Rigid joints ensure that bending moments are shared rather than isolated. This reduces peak stresses and improves structural balance. The result is a stable system that supports heavy roof and floor demands.

Lateral Load Resistance

Lateral loads from wind or seismic action challenge any structure. In a Rigid Frame System, resistance comes from the stiffness of members and connections. As lateral forces act, beams and columns bend together, developing counteracting moments. This frame action limits drift and maintains alignment. Unlike systems that rely on braces, stability comes from geometry and connection design. This makes the system effective in many environmental conditions.

Structural Continuity and Frame Action

In a rigid frame system, structural continuity defines how the entire structure carries load. Rigid beam-column joints connect members into a unified load-resisting mechanism, allowing forces and deformations to be shared. This collective behavior improves reliability, service performance, and analytical accuracy in real engineering projects.

| Aspect | Technical Explanation | Typical Applications | Key Technical Indicators (Common Ranges) | Engineering Notes |

| Structural continuity | Beams and columns are rigidly connected to form uninterrupted load paths | Industrial buildings, large commercial frames | Continuity considered in global stiffness EI/L | Must be modeled explicitly in structural analysis |

| Frame action | Loads are resisted through combined bending and shear in multiple members | Wind- and lateral-load resisting systems | Joint rotation ≈ 0 rad under service loads | Reduced effectiveness if joint rigidity is underestimated |

| Rigid joint behavior | Joints maintain near-constant angles between members | Welded steel joints, monolithic RC joints | Rotational stiffness Ks (kN·m/rad); KsL/EI ≥ 20 for fully rigid assumption | Joint strength and stiffness must be checked together |

| Internal force redistribution | Moments and forces shift between members under varying loads | Uneven live loads, changing operational use | Moment redistribution typically 10%–30% (code-dependent) | Redistribution must comply with design standards |

| Global deformation control | Whole frame deforms as a unit, limiting local excessive deflection | Long-span and multi-bay frames | Inter-story drift ratio commonly 1/300–1/500 | Insufficient continuity increases drift concentration |

| Load transfer path | Loads flow continuously from beams to columns to foundations | Integrated superstructure–foundation design | Axial force (kN), bending moment (kN·m), shear (kN) transferred together | Foundation stiffness should match frame behavior |

| Analytical reliability | Continuous frames better represent real structural behavior | Finite element and second-order analysis | Use of rigid frame models with P-Δ effects | Over-simplified models may underpredict demand |

| Serviceability performance | Reduced cracking, vibration, and long-term deflection | Public and commercial buildings | Deflection limits typically L/250–L/400 | Serviceability checks are as critical as strength |

| Long-term structural stability | Coordinated member behavior enhances durability | Long-life industrial facilities | Member stresses kept below design limits | Construction quality directly affects continuity |

Tip:For B2B projects, define rigid joint assumptions and continuity requirements early in design and align them with fabrication and erection methods. Consistent stiffness from analysis through construction helps ensure the rigid frame system delivers the intended global performance without costly redesigns later.

Common Types of Rigid Frame Systems

Fixed-Ended Rigid Frame Systems

Fixed-ended rigid frame systems rely on fully restrained beam-column and base connections to control rotation and displacement throughout the structure. This high degree of restraint increases global stiffness and reduces lateral drift, which is critical in multi-story and heavily loaded buildings. Engineers often use this system where precise deformation control is required, such as in tall industrial buildings or structures with sensitive equipment. The fixed-end condition shortens the effective column length, improving buckling resistance and allowing more efficient member sizing.

Pin-Ended Rigid Frame Systems

Pin-ended rigid frame systems introduce rotational freedom at the column bases while keeping rigid joints at beam-column intersections. This configuration reduces foundation moments and simplifies footing design without eliminating overall frame action. Engineers commonly apply it in low-rise buildings where lateral demands are moderate but clear spans are still required. By allowing controlled rotation at the base, the structure can accommodate minor foundation movement while maintaining stability through upper-level moment resistance.

Material-Based Variations

Material selection plays a defining role in rigid frame system behavior. Steel rigid frames enable long spans and rapid construction due to high strength-to-weight ratios and prefabrication. Reinforced concrete rigid frames provide inherent fire resistance, stiffness, and mass, which can improve vibration control. Engineers evaluate material properties, environmental exposure, and construction logistics together, ensuring the selected rigid frame system aligns with performance targets, durability expectations, and project scheduling constraints.

Practical Applications of Rigid Frame Systems

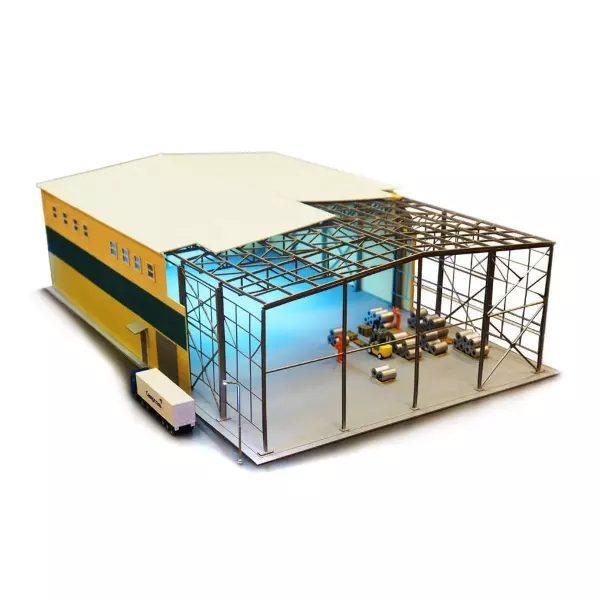

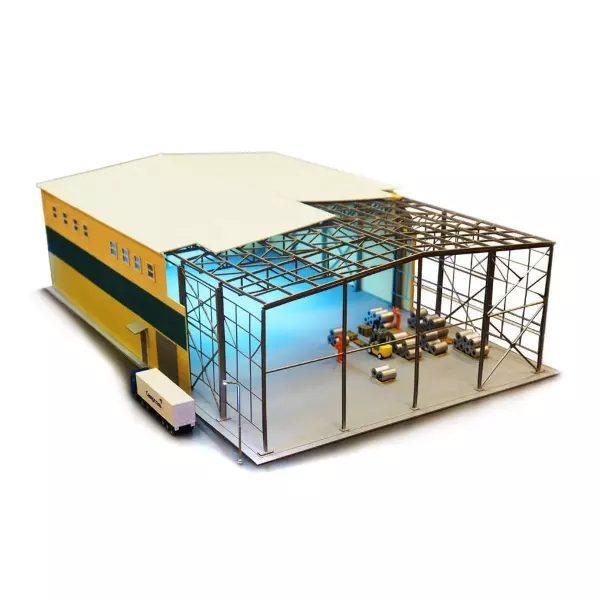

Industrial and Warehouse Buildings

In industrial and warehouse buildings, a Rigid Frame System is selected not only for clear spans but also for its ability to manage high roof loads and dynamic operational demands. Engineers often design these frames to accommodate overhead cranes, suspended utilities, and racking systems by controlling deflection limits and member stiffness. Steel rigid frames allow long bay spacing, which improves forklift circulation and storage density. From a structural planning perspective, the predictable load paths of rigid frames simplify future upgrades, such as increased floor loads or added equipment, without altering the primary structure.

Commercial and Public Buildings

For commercial and public buildings, a Rigid Frame System provides a balance between structural safety and architectural freedom. Engineers design these frames to handle crowd-induced live loads, roof equipment, and large roof spans while maintaining serviceability limits for vibration and deflection. The absence of interior columns supports flexible seating, exhibition layouts, and multipurpose use. From a design standpoint, rigid frames integrate well with façades, glazing systems, and long-span roofs, allowing architects to combine open interiors with visually expressive building envelopes.

Specialized and Large-Span Structures

Specialized and large-span structures place unique demands on structural systems, which is why a Rigid Frame System is frequently adopted. Engineers use deep or tapered members to control bending stresses over long spans while maintaining reasonable material efficiency. Large door openings, such as hangar doors, are structurally feasible because loads can bypass openings through frame action. In environments with snow, wind, or industrial exposure, rigid frames provide consistent performance by distributing extreme loads across multiple members, ensuring stability even under highly variable operating conditions.

Key Advantages of Using a Rigid Frame System

Structural Strength and Stability

A Rigid Frame System achieves structural strength through the interaction of member stiffness and rigid joints rather than isolated elements. Beams and columns work together to resist bending, shear, and axial forces, which limits stress concentration and improves fatigue performance. In steel rigid frames, high section modulus and controlled slenderness ratios enhance load capacity. In reinforced concrete frames, continuity of reinforcement ensures stable force transfer. This integrated behavior supports consistent performance under varying service loads, making the system suitable for long-term, high-reliability structures.

Design Flexibility and Clear Spans

Design flexibility in a Rigid Frame System comes from its ability to achieve long, column-free spans while maintaining structural integrity. Engineers can size members to span wide bays without relying on internal supports, enabling adaptable floor layouts. This allows mechanical systems, storage equipment, and circulation paths to change over time without structural modification. Clear spans also improve space efficiency and daylight access. From a planning perspective, this adaptability supports phased expansion, mixed-use layouts, and evolving operational requirements without compromising structural performance.

Construction Efficiency and Long-Term Value

Construction efficiency and lifecycle value are major reasons why rigid frame systems are favored in industrial and commercial projects. Prefabrication, standardized connections, and predictable structural behavior reduce on-site uncertainty. Over time, these advantages translate into lower operational disruption, stable performance, and stronger return on investment.

| Dimension | Technical Explanation | Practical Applications | Key Technical Metrics (Typical Ranges) | Engineering & Management Notes |

| Prefabrication level | Primary frame members fabricated off-site under controlled conditions | Steel rigid frame warehouses, factories | Fabrication tolerance ±2–3 mm (steel members) | Requires early design freeze and shop drawing accuracy |

| Construction speed | Reduced on-site assembly time due to pre-engineered components | Fast-track industrial projects | Erection rate often 20–40% faster than cast-in-place RC frames | Crane planning and logistics coordination are critical |

| Labor efficiency | Fewer on-site labor hours due to bolted or welded assemblies | Remote or labor-constrained regions | On-site labor reduction commonly 15–30% | Skilled erection crews still required for joints |

| Quality control | Factory fabrication ensures consistent member geometry and welding quality | Projects with strict performance standards | Weld quality per AWS D1.1 / ISO 3834 | QA/QC responsibility shifts toward fabrication stage |

| Schedule predictability | Parallel fabrication and foundation work shorten overall timeline | Large-scale B2B developments | Schedule compression often 10–25% | Delays usually linked to design changes, not framing |

| Structural adaptability | Clear-span frames allow future layout changes without structural alteration | Warehouses, logistics centers | Typical clear spans 20–90 m (steel rigid frames) | Allowance for future loads should be planned upfront |

| Lifecycle performance | Stable stiffness and load paths reduce long-term structural intervention | Long-life industrial facilities | Design life commonly 50 years (ISO/EN standards) | Periodic inspection focuses on connections and coatings |

| Maintenance demand | Fewer secondary structural elements reduce inspection complexity | High-bay industrial buildings | Coating maintenance cycles 10–20 years (environment dependent) | Corrosion protection strategy impacts lifecycle cost |

| Cost efficiency over time | Higher initial efficiency offsets operational and modification costs | Owner-operated facilities | Lifecycle cost savings often realized after 5–10 years (project-specific) | Value best assessed using life-cycle cost analysis (LCCA) |

Tip:For B2B owners, maximum value comes from aligning rigid frame design with long-term operational plans. Defining future load allowances, expansion potential, and maintenance strategy during early design helps ensure that construction speed gains translate into measurable lifecycle savings rather than short-term benefits only.

Conclusion

A Rigid Frame System is a foundational solution in modern construction, combining structural strength, stability, and design flexibility in one integrated framework. Through rigid joints and continuous members, it supports large spans, open interiors, and reliable performance across industrial, commercial, and public buildings. When applied correctly, it delivers long-term value through efficient construction and adaptable use. Qingdao qianchengxin Construction Technology Co., Ltd. provides rigid frame systems with precise engineering, high-quality fabrication, and flexible solutions, helping clients build durable structures that meet performance goals and support future growth.

FAQ

Q: What is a Rigid Frame System?

A: A Rigid Frame System uses rigid beam-column joints to resist vertical and lateral loads as one unified structure.

Q: Why is a Rigid Frame System widely used?

A: A Rigid Frame System offers strength, stability, and clear spans for flexible building layouts.

Q: Where is a Rigid Frame System commonly applied?

A: A Rigid Frame System is common in warehouses, factories, halls, and large commercial buildings.

Q: How does a Rigid Frame System resist lateral loads?

A: A Rigid Frame System resists wind and seismic forces through joint stiffness and frame action.

Q: Is a Rigid Frame System cost-effective long term?

A: A Rigid Frame System reduces lifecycle costs through prefabrication and adaptable space design.